Prehistory

The territory of modern-day Georgia was inhabited by Homo erectus since the Paleolithic Era. The proto-Georgian tribes first appear in written history in the 12th century BC. The earliest evidence of wine to date has been found in Georgia, where 8000-year old wine jars were uncovered. Archaeological finds and references in ancient sources also reveal elements of early political and state formations characterized by advanced metallurgy and goldsmith techniques that date back to the 7th century BC and beyond.In fact, early metallurgy started in Georgia during the 6th millennium BC, associated with the Shulaveri-Shomu culture.

Antiquity

The classical period saw the rise of a number of early Georgian states, the principal of which was Colchis in the west and Iberia in the east. In Greek mythology, Colchis was the location of the Golden Fleece sought by Jason and the Argonauts in Apollonius Rhodius' epic tale Argonautica. The incorporation of the Golden Fleece into the myth may have derived from the local practice of using fleeces to sift gold dust from rivers. In the 4th century BC, a kingdom of Iberia – an early example of advanced state organization under one king and an aristocratic hierarchy – was established.

After the Roman Republic completed its brief conquest of what is now Georgia in 66 BC, the area became a primary objective of what would eventually turn out to be over 700 years of protracted Irano–Roman geo-political rivalry and warfare. From the first centuries A.D, the cult of Mithras, pagan beliefs, and Zoroastrianism were commonly practised in Georgia. In 337 AD King Mirian III declared Christianity as the state religion, giving a great stimulus to the development of literature, arts, and ultimately playing a key role in the formation of the unified Georgian nation, The acceptance led to the slow but sure decline of Zoroastrianism, which until the 5th century AD, appeared to have become something like a second established religion in Iberia (eastern Georgia), and was widely practised there.

Middle Ages up to Early Modern Period

Located on the crossroads of protracted Roman–Persian wars, the early Georgian kingdoms disintegrated into various feudal regions by the early Middle Ages. This made it easy for the remaining Georgian realms to fall prey to the early Muslim conquests in the 7th century.

Bagratid Iberia

The extinction of the different Iberian royal dynasties, such as Guaramids and the Chosroids, and also the Abbasid preoccupation with their own civil wars and conflict with the Byzantine Empire, let the Bagrationi family to grown in prominence. The head of the Bagrationi dynasty Ashot I of Iberia (r.813–826), who had migrated to the former southwestern territories of Iberia, came to rule over Tao-Klarjeti and restored the Principate of Iberia in 813. The sons and grandsons of Ashot I established three separate branches, frequently struggling with each other and with neighboring rulers. The Kartli line prevailed; in 888 Adarnase IV of Iberia (r.888–923) restored the indigenous royal authority dormant since 580. Despite the revitalization of the Iberian monarchy, remaining Georgian lands were divided among rival authorities, with Tbilisi remaining in Arab hands.

Kingdom of Abkhazia

An Arab incursion into western Georgia led by Marwan II, was repelled by Leon I (r.720–740) jointly with his Lazic and Iberian allies in 736. Leon I then married Mirian’s daughter, and a successor, Leon II exploited this dynastic union to acquire Lazica in the 770s. The successful defense against the Arabs, and new territorial gains, gave the Abkhazian princes enough power to claim more autonomy from the Byzantine Empire. Towards circa 778, Leon II (r.780–828) won his full independence with the help of the Khazars and was crowned as the king of Abkhazia. After obtaining of the state independence, the matter of the church independence became the main problem. In the early 9th century Abkhazian Church broke away from Constantinople and recognized the authority of the Catholicate of Mtskheta; Georgian language replaced Greek as the language of literacy and culture. The most prosperous period of the Abkhazian kingdom was between 850 and 950. A bitter civil war and feudal revolts which began under Demetrius III (r. 967–975) led the kingdom into complete anarchy under the unfortunate king Theodosius III the Blind (r.975–978). A period of unrest ensued, which ended as Abkhazia and eastern Georgian states were unifiedunder a single Georgian monarchy, ruled by King Bagrat III of Georgia (r.975–1014), due largely to the diplomacy and conquests of his energetic foster-father David III of Tao (r. 966–1001).

United Georgian monarchy

The stage of feudalism's development and struggle against common invaders as much as common belief of various Georgian states had an enormous importance for spiritual and political unification of Georgia feudal monarchy under the Bagrationi dynasty in 11th century.

The Kingdom of Georgia reached its zenith in the 12th to early 13th centuries. This period during the reigns of David IV (r.1089–1125) and his granddaughter Tamar (r.1184–1213) has been widely termed as Georgia's Golden Age or the Georgian Renaissance. This early Georgian renaissance, which preceded its Western European analogue, was characterized by impressive military victories, territorial expansion, and a cultural renaissance in architecture, literature, philosophy and the sciences. The Golden age of Georgia left a legacy of great cathedrals, romantic poetry and literature, and the epic poem "The Knight in the Panther's Skin", the latter which is considered a national epic.

David suppressed dissent of feudal lords and centralized the power in his hands to effectively deal with foreign threats. In 1121, he decisively defeated much larger Turkish armies during the Battle of Didgori and liberated Tbilisi.

The 29-year reign of Tamar, the first female ruler of Georgia, is considered the most successful in Georgian history. Tamar was given the title "king of kings" (mepe mepeta). She succeeded in neutralizing opposition and embarked on an energetic foreign policy aided by the downfall of the rival powers of the Seljuks and Byzantium. Supported by a powerful military élite, Tamar was able to build on the successes of her predecessors to consolidate an empire which dominated the Caucasus, and extended over large parts of present-day Azerbaijan, Armenia, and eastern Turkey as well as parts of northern Iran, until its collapse under the Mongol attacks within two decades after Tamar's death in 1213.

The revival of the Kingdom of Georgia was set back after Tbilisi was captured and destroyed by the Khwarezmian leader Jalal ad-Din in 1226. The Mongols were expelled by George V of Georgia (r.1299–1302), son of Demetrius II of Georgia (r.1270–1289), who was named "Brilliant" for his role in restoring the country's previous strength and Christian culture. George V was the last great king of the unified Georgian state. After his death, different local rulers fought for their independence from central Georgian rule, until the total disintegration of the Kingdom in the 15th century. Georgia was further weakened by several disastrous invasions by Tamerlane. Invasions continued, giving the kingdom no time for restoration, with both Black and White sheep Turkomans constantly raiding its southern provinces.

Queen Tamar of Georgia presided over the "Golden Age" of the medieval Georgian monarchy. Her position as the first woman to rule Georgia in her own right was emphasized by the title "Mepe mepeta" ("King of Kings").

Tripartite division

The Kingdom of Georgia collapsed into anarchy by 1466 and fragmented into three independent kingdoms and five semi-independent principalities. Neighboring large empires subsequently exploited the internal division of the weakened country, and beginning in the 16th century up to the late 18th century, Safavid Iran (and successive Iranian Afsharid and Qajar dynasties) and Ottoman Turkey subjugated the eastern and western regions of Georgia, respectively.

The rulers of regions that remained partly autonomous organized rebellions on various occasions. However, subsequent Iranian and Ottoman invasions further weakened local kingdoms and regions. As a result of incessant wars and deportations, the population of Georgia dwindled to 250,000 inhabitants at the end of the 18th century. Eastern Georgia (Safavid Georgia), composed of the regions of Kartli and Kakheti, had been under Iranian suzerainty since 1555 following the Peace of Amasya signed with neighbouring rivalling Ottoman Turkey. With the death of Nader Shah in 1747, both kingdoms broke free of Iranian control and were reunified through a personal unionunder the energetic king Heraclius II in 1762. Heraclius, who had risen to prominence through the Iranian ranks, was awarded the crown of Kartli by Nader himself in 1744 for his loyal service to him. Heraclius nevertheless stabilized Eastern Georgia to a degree in the ensuing period and was able to guarantee its autonomy throughout the Iranian Zand period.

In 1783, Russia and the eastern Georgian Kingdom of Kartli-Kakheti signed the Treaty of Georgievsk, by which Georgia abjured any dependence on Persia or another power, and made the kingdom a protectorate of Russia, which guaranteed Georgia's territorial integrity and the continuation of its reigning Bagrationi dynasty in return for prerogatives in the conduct of Georgian foreign affairs.

However, despite this commitment to defend Georgia, Russia rendered no assistance when the Iranians invaded in 1795, capturing and sacking Tbilisi while massacring its inhabitants, as the new heir to the throne sought to reassert Iranian hegemony over Georgia. Despite a punitive campaign subsequently launched against Qajar Iran in 1796, this period culminated in the 1801 Russian violation of the Treaty of Georgievsk and annexation of eastern Georgia, followed by the abolition of the royal Bagrationi dynasty, as well as the autocephaly of the Georgian Orthodox Church. Pyotr Bagration, one of the descendants of the abolished house of Bagrationi, would later join the Russian army and rise to be a prominent general in the Napoleonic wars.

Georgia in the Russian Empire

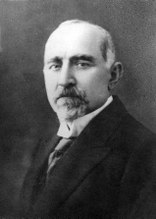

Pyotr Bagration, Georgian prince of the royal Bagrationi dynasty

On 22 December 1800, Tsar Paul I of Russia, at the alleged request of the Georgian King George XII, signed the proclamation on the incorporation of Georgia (Kartli-Kakheti) within the Russian Empire, which was finalized by a

King George XII was the last king of Kartli and Kakheti, which was annexed by Russia in 1801.

decree on 8 January 1801, and confirmed by Tsar Alexander I on 12 September 1801. The Bagrationiroyal family was deported from the kingdom. The Georgian envoy in Saint Petersburg reacted with a note of protest that was presented to the Russian vice-chancellor Prince Kurakin. In May 1801, under the oversight of General Carl Heinrich von Knorring, Imperial Russia transferred power in eastern Georgia to the government headed by General Ivan Petrovich Lazarev. The Georgian nobility did not accept the decree until 12 April 1802, when Knorring assembled the nobility at the Sioni Cathedral and forced them to take an oath on the Imperial Crown of Russia. Those who disagreed were temporarily arrested.

In the summer of 1805, Russian troops on the Askerani River near Zagam defeated the Iranian army during the 1804–13 Russo-Persian War and saved Tbilisi from reconquest now that it was officially part of the Imperial territories. Russian suzerainty over eastern Georgia was officially finalized with Iran in 1813 following the Treaty of Gulistan. Following the annexation of eastern Georgia, the western Georgian kingdom of Imereti was annexed by Tsar Alexander I. The last Imeretian king and the last Georgian Bagrationi ruler, Solomon II, died in exile in 1815, after attempts to rally people against Russia and to enlist foreign support against the latter, had been in vain. From 1803 to 1878, as a result of numerous Russian wars now against Ottoman Turkey, several of Georgia's previously lost territories – such as Adjara – were recovered, and also incorporated into the empire. The principality of Guria was abolished and incorporated into the Empire in 1829, while Svaneti was gradually annexed in 1858. Mingrelia, although a Russian protectorate since 1803, was not absorbed until 1867.

Declaration of independence

After the Russian Revolution of 1917, the Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic was established with Nikolay Chkheidze acting as its president. The federation consisted of three nations: Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan. As the Ottomans advanced into the Caucasian territories of the crumbling Russian Empire, Georgia declared independence on 26 May 1918. The Menshevik Social Democratic Party of Georgia won the parliamentary election and its leader, Noe Zhordania, became prime minister. Despite the Soviet takeover, Zhordania was recognized as the legitimate head of the Georgian Government by France, UK, Belgium, and Poland through the 1930s.

The 1918 Georgian–Armenian War, which erupted over parts of Georgian provinces populated mostly by Armenians, ended because of British intervention. In 1918–1919, Georgian general Giorgi Mazniashvili led an attack against the White Army led by Moiseev and Denikin in order to claim the Black Sea coastline from Tuapse to Sochi and Adler for the independent Georgia. The country's independence did not last long. Georgia was under British protection from 1918–1920.

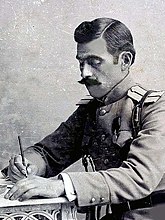

Nikolay Chkheidze, Russian, Transcaucasian and Georgian politician

Noe Zhordania, first prime minister of Georgia

General Giorgi Mazniashvili

Georgia in the Soviet Union

In February 1921, during the Russian Civil War, the Red Army advanced into Georgia and brought the local Bolsheviks to power. The Georgian army was defeated and the Social Democratic government fled the country. On 25 February 1921, the Red Army entered Tbilisi and established a government of workers' and peasants' soviets with Filipp Makharadze as acting head of state. Georgia was incorporated into the Transcaucasian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic, alongside Armenia and Azerbaijan, in 1921 which in 1922 would become a founding member of the Soviet Union.

There remained significant opposition to the Bolsheviks in Georgia, which was unindustrialized and viewed as socially backward, and this culminated in the August Uprising of 1924. Soviet rule was firmly established only after the insurrection was swiftly defeated. Georgia would remain an unindustrialized periphery of the USSR until the first five-year plan when it would become a major center for textile goods. Later, in 1936, the TSFSR was dissolved and Georgia emerged as a union republic: the Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic.

Joseph Stalin, an ethnic Georgian born Ioseb Besarionis Dze Jugashvili was prominent among the Bolsheviks.[67] Stalin was to rise to the highest position, leading the Soviet Union from the mid–1920s until his death on 5 March 1953.

In June 1941, Germany invaded the Soviet Union on an immediate course towards Caucasian oil fields and munitions factories. They never reached Georgia, however, and almost 700,000 Georgians fought in the Red Army to repel the invaders and advance towards Berlin. Of them, an estimated 350,000 were killed.

After Stalin's death, Nikita Khrushchev became the leader of the Soviet Union and implemented a policy of de-Stalinization. This was nowhere else more publicly and violently opposed than in Georgia, where in 1956 riots broke out upon the release of Khruschev's public denunciation of Stalin and led to the death of nearly 100 students.

Throughout the remainder of the Soviet period, Georgia's economy continued to grow and experience significant improvement, though it increasingly exhibited blatant corruption and alienation of the government from the people. With the beginning of perestroika in 1986, the Georgian Communist leadership proved so incapable of handling the changes that most Georgians, including rank and file Communists, concluded that the only way forward was a break from the existing Soviet system.

Georgia after restoration of independence

The Rose Revolution, 2003

On 9 April 1991, shortly before the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Supreme Council of Georgia declared independence after a referendum held on 31 March 1991. On 26 May 1991, Gamsakhurdia was elected as the first President of independent Georgia. Gamsakhurdia stoked Georgian nationalism and vowed to assert Tbilisi's authority over regions such as Abkhazia and South Ossetia that had been classified as autonomous oblasts under the Soviet Union.

He was soon deposed in a bloody coup d'état, from 22 December 1991 to 6 January 1992. The coup was instigated by part of the National Guards and a paramilitary organization called "Mkhedrioni" ("horsemen"). The country became embroiled in a bitter civil war, which lasted until nearly 1995. Eduard Shevardnadze (Soviet Minister of Foreign Affairs from 1985 to 1991) returned to Georgia in 1992 and joined the leaders of the coup—Tengiz Kitovani and Jaba Ioseliani—to head a triumvirate called "The State Council".

Simmering disputes within two regions of Georgia, Abkhazia and South Ossetia, between local separatists and the majority Georgian populations, erupted into widespread inter-ethnic violence and wars. Supported by Russia, Abkhazia, and South Ossetia achieved de facto independence from Georgia, with Georgia retaining control only in small areas of the disputed territories. In 1995, Shevardnadze was officially elected as president of Georgia.

During the War in Abkhazia (1992–1993), roughly 230,000 to 250,000 Georgians were expelled from Abkhazia by Abkhaz separatists and North Caucasian volunteers (including Chechens). Around 23,000 Georgians fled South Ossetia as well, and many Ossetian families were forced to abandon their homes in the Borjomi region and moved to Russia.

In 2003, Shevardnadze (who won re-election in 2000) was deposed by the Rose Revolution, after Georgian opposition and international monitors asserted that 2 November parliamentary elections were marred by fraud. The revolution was led by Mikheil Saakashvili, Zurab Zhvania and Nino Burjanadze, former members and leaders of Shevardnadze's ruling party. Mikheil Saakashvili was elected as President of Georgia in 2004.

Following the Rose Revolution, a series of reforms were launched to strengthen the country's military and economic capabilities. The new government's efforts to reassert Georgian authority in the southwestern autonomous republic of Ajaria led to a major crisis early in 2004. Success in Ajaria encouraged Saakashvili to intensify his efforts, but without success, in breakaway South Ossetia.

US Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice holding a joint press conference with Georgian president Mikheil Saakashvili during the Russo–Georgian war

These events, along with accusations of Georgian involvement in the Second Chechen War, resulted in a severe deterioration of relations with Russia, fuelled also by Russia's open assistance and support to the two secessionist areas. Despite these increasingly difficult relations, in May 2005 Georgia and Russia reached a bilateral agreement by which Russian military bases (dating back to the Soviet era) in Batumi and Akhalkalaki were withdrawn. Russia withdrew all personnel and equipment from these sites by December 2007 while failing to withdraw from the Gudauta base in Abkhazia, which it was required to vacate after the adoption of the Adapted Conventional Armed Forces in Europe Treaty during the 1999 Istanbul summit.

Russo–Georgian War and since

Tensions between Georgia and Russia began escalating in April 2008. bomb explosion on 1 August 2008 targeted a car transporting Georgian peacekeepers. South Ossetians were responsible for instigating this incident, which marked the opening of hostilities and injured five Georgian servicemen. In response,several South Ossetian militiamen were hit. South Ossetian separatists began shelling Georgian villages on 1 August. These artillery attacks caused Georgian servicemen to return fire periodically since 1 August.

At around 19:00 on 7 August 2008, Georgian president Mikheil Saakashvili announced a unilateral ceasefire and called for peace talks.However, escalating assaults against Georgian villages (located in the South Ossetian conflict zone) were soon matched with gunfire from Georgian troops,[ who then proceeded to move in the direction of the capital of the self-proclaimed Republic of South Ossetia (Tskhinvali) on the night of 8 August, reaching its centre in the morning of 8 August. One Georgian diplomat told Russian newspaper Kommersant on 8 August that by taking control of Tskhinvali, Tbilisi wanted to demonstrate that Georgia wouldn't tolerate killing of Georgian citizens. According to Russian military expert Pavel Felgenhauer, the Ossetian provocation was aimed at triggering the Georgian response, which was needed as a pretext for premeditated Russian military invasion. According to Georgian intelligence, and several Russian media reports, parts of the regular (non-peacekeeping) Russian Army had already moved to South Ossetian territory through the Roki Tunnel before the Georgian military action.

Russia accused Georgia of "aggression against South Ossetia", and launched a large-scale land, air and sea invasion of Georgia with the pretext of "peace enforcement" operation on 8 August 2008. Russian airstrikes against targets within Georgia were also launched.Abkhaz forces opened a second front on 9 August by attacking the Kodori Gorge, held by Georgia. Tskhinvali was seized by the Russian military by 10 August. Russian forces occupied the Georgian cities of Zugdidi,Senaki, Poti, and Gori (the last one after the ceasefire agreement was negotiated). Russian Black Sea Fleet blockaded the Georgian coast.

A campaign of ethnic cleansing against Georgians in South Ossetia was conducted by South Ossetians, with Georgian villages around Tskhinvali being destroyed after the war had ended. The war displaced 192,000 people, and while many were able to return to their homes after the war, a year later around 30,000 ethnic Georgians remained displaced. In an interview published in Kommersant, South Ossetian leader Eduard Kokoity said he would not allow Georgians to return.

President of France Nicolas Sarkozy negotiated a ceasefire agreement on 12 August 2008. On 17 August, Russian president Dmitry Medvedev announced that Russian forces would begin to pull out of Georgia the following day. Russia recognised Abkhazia and South Ossetia as separate republics on 26 August. In response to Russia's recognition, the Georgian government severed diplomatic relations with Russia. Russian forces left the buffer areas bordering Abkhazia and South Ossetia on 8 October, and the European Union Monitoring Mission in Georgia was dispatched to the buffer areas. Since the war, Georgia has maintained that Abkhazia and South Ossetia are Russian-occupied Georgian territories.

On 30 September 2009, the European Union–sponsored Independent International Fact-Finding Mission on the Conflict in Georgia stated that, while preceded by months of mutual provocations, "open hostilities began with a large-scale Georgian military operation against the town of Tskhinvali and the surrounding areas, launched in the night of 7 to 8 August 2008.